Measuring Impact

Part 1

How is Mercy Ships helping address the global surgery crises? What impact do we have on the communities we serve? Where should we be focusing our future projects? These are complex but key questions our organization must consider and explore in order to maximize our ability to bring hope and healing to those in desperate need.

Such questions are not only hard because of their scope and importance, but also because of their underlying complexity. Hypotheses conjured up to test. Data collected to support or dismiss our speculations. Analysis performed to measure the weight of the evidence. And lastly, a new path charted that aligns with the conclusions elucidated.

Needless to say, the journey of introspection is long and arduous, which is why Mercy Ships has been putting a greater and greater emphasis on research into these questions. In the following paragraphs, you will encounter an example of that research in action and a broader look at past, present, and future impact evaluation.

Testing Assumptions

In the past, we assumed that we were reaching the poorest individuals because of the relatively low overall wealth of a host country, but, as part of a research project from 2014-2016, we tested that assumption through demographic analysis of our patients.

It turns out our assumption was wrong.

—

In Madagascar, the Africa Mercy was docked in the eastern port city, Toamasina, which is eight hours by road from the capital city, Antananarivo. In the first field service (October 2014–June 2015), Mercy Ships used their usual, centralized selection strategy, which aimed to find 70% of patients from Toamasina and 30% from the capital (Antananarivo), in addition to two remote cities (Mahajanga and Toliara). As Figure 1 shows, 60% of our patients that year came from the richest 20% of the Malagasy population. Only 4% came from the poorest.

So we responded. For the second year in Madagascar, we changed things around in order to better align with the expectations of the Malagasy government, who wanted all of their citizens to have equal access to Mercy Ships. Between August 2015 and June 2016, a decentralized selection strategy was used, aiming to find only 30% of patients from Toamasina and 70% from the capital, in addition to 10 remote locations. For the decentralized screening strategy, 10 remote sites were identified in collaboration with the Ministry of Health as sufficient to cover the majority of the country’s population (see map).

And it worked.

The change in selection strategy from centralized to decentralized selection tripled the proportion of patients who came from the poorest part of the Malagasy population [1]. As a result of rigorously testing our original assumption, in following field services Mercy Ships has employed patient selection strategies that strive for greater equity of access to surgical care for all citizens of a host nation.

Mercy Ships Impact

During 38 years of operation, Mercy Ships has developed quality programs to help address the overwhelming, global need for surgery. But are we accomplishing what we want to accomplish? As the example from Madagascar shows, we need to ask these questions and continue to become excellent servants of the people we are called to help. This is the goal of Mercy Ships’ newly-formed impact evaluation project.

—

To accomplish this, Mercy Ships is partnering with the Centre for Global Surgery Evaluation at the Massachusetts Eye and Ear and Harvard Medical School. These institutions will assist Mercy Ships in learning about the medical, social, and financial impact of surgical and capacity-building projects. This information will allow Mercy Ships to test assumptions, evaluate outcomes, and improve project design for future field service deployments.

Current Evaluation Practices

Currently, Mercy Ships collects detailed data on project outputs along with anecdotal evidence of project results. Project outcome information primarily comes in the form of surgical statistics (number of surgeries, patients, participants trained, etc.), feedback from training participants gathered during semi-structured interviews, and review of surgical projects when the Africa Mercy returns to a previous host country. More robust information regarding the sustainability and impact of surgical and training projects is needed to understand the longer-term results of current projects as well as what changes are needed in project design.

Mercy Ships measures indicators of success at various levels for Direct Medical Services (DMS) and Medical Capacity Building (MCB).

These include:

- Short-term Indicators of Success

- DMS: Number of patients, surgeries, and non-surgical interventions.

- MCB: Changes from pre- and post-test results, observations by project facilitators (instructors).

- Intermediate-term Indicators of Success

- DMS: Post-operative regained range of motion for Plastics and Orthopaedic patients, visual acuity for eye patients, disability assessments, etc.

- MCB: Three to six months after initial training is completed, the project facilitator discusses factors that aid or limit implementation of newly learned knowledge and skills.

- Long-term Indicators of Success

- DMS: Patient interviews and occasional follow-up assessments of surgical outcomes.

- MCB: Twelve to twenty-four months after ship departure, a team returns to interview project participants and hospital leadership regarding the change in practice since training and any resulting outcomes in patient care.

Importantly, many local hospitals may not have the best methods for observing, recording, and reporting on standard hospital metrics, such as complication and mortality rates. This limitation has limited Mercy Ships’ evaluation efforts to compare itself to the health care outcomes of the host nation. Mercy Ships’ new evaluation goals, as defined by this impact evaluation project, will set up a sustainable methodology and organizational infrastructure that can reliably collect the necessary information for measuring the effect of Mercy Ships’ service in a nation.

Aim 1: Determine the medical and financial impact of Mercy Ships Direct Medical Services.

Aim 2: Determine the short- and long-term impacts of Mercy Ships Medical Capacity-Building Projects.

The evaluation of project outcomes and assumptions is not a singular event, but rather a process throughout project development and implementation. Understanding this process and the influence of external factors is important in the creation of an evaluation methodology that is valid and robust for both Direct Medical Services and Medical Capacity Building.

Evaluation Project Objectives

In the process of achieving the goals listed above, Mercy Ships is assisting the Centre for Global Surgery Evaluation in the development of tools to verify the expected results of both medical and capacity-building projects.

Project Objective: Develop objective, scalable, valid, and replicable tools and processes for impact evaluation of Mercy Ships Direct Medical Services and Medical Capacity-Building Projects in the host nations.

| Project | Outcomes to Verify |

| Direct Medical Services |

|

| Medical Capacity Building |

|

The Mercy Ships Impact Evaluation Team will be posting a series of updates over the next several years. For more information on current projects and programs email msca@mercyships.ca.

Reference

- White MC, Hamer M, Biddell J, et al Facilitating access to surgical care through a decentralised case-finding strategy: experience in Madagascar BMJ Global Health 2017;2:e000427.

Mercy Ships Welcomes Presidential Visit on board, in Toamasina Harbor

Presidential Visit: Malagasy president His Excellency Andry Nirina Rajoelina visited patients and volunteers on board Mercy Ships’ hospital vessel to see for himself the lives being transformed.

Day of the Seafarer: One Maritime Volunteer’s Story

On this Day of the Seafarer, Mercy Ships wants to honor all the people like Ishaka, volunteer assistant bosun on board the Global Mercy.

An Electrician’s Journey to Finding Purpose and Professional Growth

When Jean Jacques Diouf came on board for the 1st time, he’d packed his suitcase with enough supplies for one week. Learn more about his professional growth!

THE MSC FOUNDATION, THE MSC GROUP AND MERCY SHIPS INTERNATIONAL JOIN FORCES TO BUILD A NEW HOSPITAL SHIP

The new purpose-built hospital ship will expand the impact of Mercy Ships’ life-changing surgeries, anaesthetic care and surgical education for future generations of patients and healthcare professionals in sub-Saharan Africa.

The Woman Who Forged Her Way Through Walls: Florence Bangura’s Story

Florence’s journey from oldest to newest Mercy Ship came full circle when she met the Global Mercy™ in 2023, the same year that the purpose-built hospital ship began welcoming its patients on board. Today, you can find Florence, now 49 years old, down in the engine room as a hotel engineering assistant.

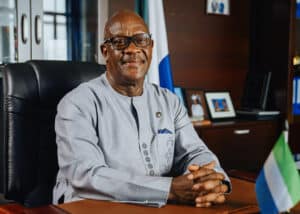

Transforming Sierra Leone’s Healthcare: A Vision for Safe and Affordable Surgery

As experts from the surgical and healthcare world gather for the 64th Annual Conference and Scientific Meeting of the West African College of Surgeons in Sierra Leone this week, a profound dedication to advancing surgical knowledge and practice in the region is palpable. At the forefront of discussions lies the conference’s pivotal theme: access to safe and affordable surgical and anesthetic care in West Africa. This theme highlights the pressing need to address disparities in healthcare capabilities and capacities across the region, especially the critical importance of equitable access to quality surgical interventions.

Share

Related Posts

Africa Celebration

The Africa Celebration is a moment to pause and give thanks for 30 years of partnership, filled with stories of hope and healing.

Raising the Bar for Safe Surgical Care on World Health Day

Dr. Juliette Tuakli speaks on what the theme for this year’s World Health Day, “Health for All,” really looks like on the continent of Africa.

The Africa Mercy Arrives in Madagascar to Bring Hope and Healing Anew

Freshly refitted hospital ship, the upgraded Africa Mercy® has arrived at the island nation to build on the charity’s longstanding collaboration and will provide specialized surgeries in various fields, including maxillofacial and ear nose and throat, general, pediatric specialized general, pediatric orthopedic, cataract surgery, and reconstructive plastics.

International Symposium and Dakar Declaration

Learn more about the International Symposium and Dakar Declaration that were hosted in Dakar, Senegal, on Friday, May 6, 2022.

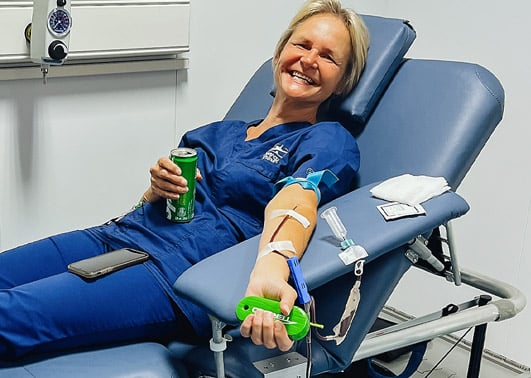

World Blood Donor Day

In a traditional medical setting, donors can be recruited ahead of time at blood drives, and their life-saving gifts can be sealed in bags and stored for later use. A Mercy Ships hospital, cut off from resources back home, is different. It must rely on the people who staff it.

Transforming Sierra Leone’s Healthcare: A Vision for Safe and Affordable Surgery

As experts from the surgical and healthcare world gather for the 64th Annual Conference and Scientific Meeting of the West African College of Surgeons in Sierra Leone this week, a profound dedication to advancing surgical knowledge and practice in the region is palpable. At the forefront of discussions lies the conference’s pivotal theme: access to safe and affordable surgical and anesthetic care in West Africa. This theme highlights the pressing need to address disparities in healthcare capabilities and capacities across the region, especially the critical importance of equitable access to quality surgical interventions.